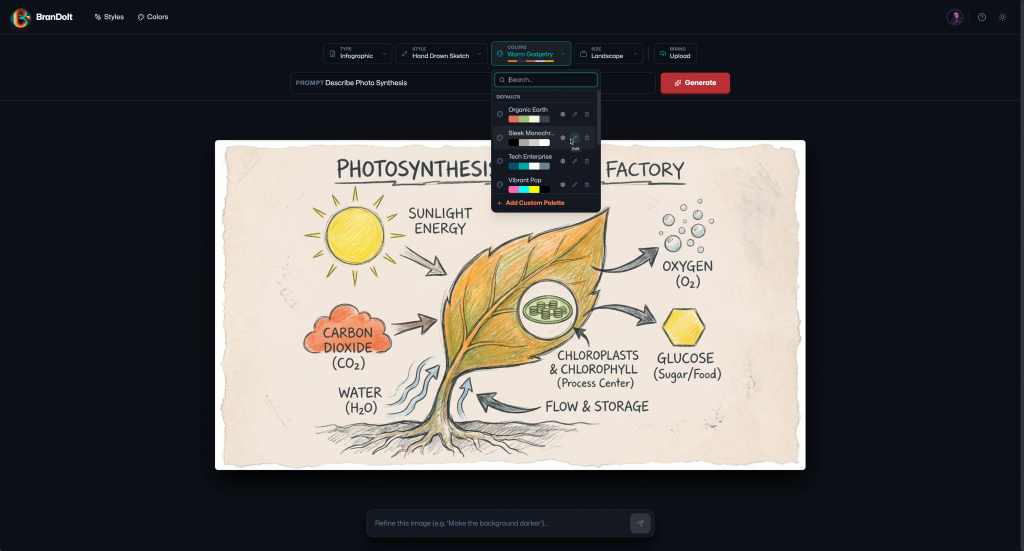

I started BranDoIt as a prototype inside Google AI Studio. It was the kind of thing that feels magical in the moment. A prompt, a few UI tweaks, and suddenly you have something that generates brand‑consistent graphics. As a matter of fact, it was part of my Vibe Code This series.

Then I tried to make it usable by other people at brandoit.onrender.com. That is where the work changed. Not more difficult in a dramatic way, but broader, more deliberate, and far less forgiving.

The prototype mindset

The prototype from AI Studio which was called BananaBrand ran on my machine, assumed my API key, and stored state in the browser. That is a perfectly reasonable way to explore an idea.

A product, however, has different goals. It has to work for people I have never met, on networks and devices I do not control, with very little patience for confusing behavior. It has to protect user data, control costs, and survive refreshes, logouts, and bad inputs. It’s a whole new set of responsibilities.

Are you ready for those? Let’s explore some of what you need to think about you may have not considered.

Vibe Coding for Developers

Chatbots are great, but they can only take you so far. Eventually you’re going to have to take this further, learning to use tools like GitHub, and platforms that handle vibe coding more powerfully like Cursor or Visual Studio Code.

They offer superior multi-language prompting with an understanding of your entire project’s code. Most chatbots will only generate single page code files. A more professional tool will help you solve bigger projects that span multiple files and connect to services better, but they do require some learning.

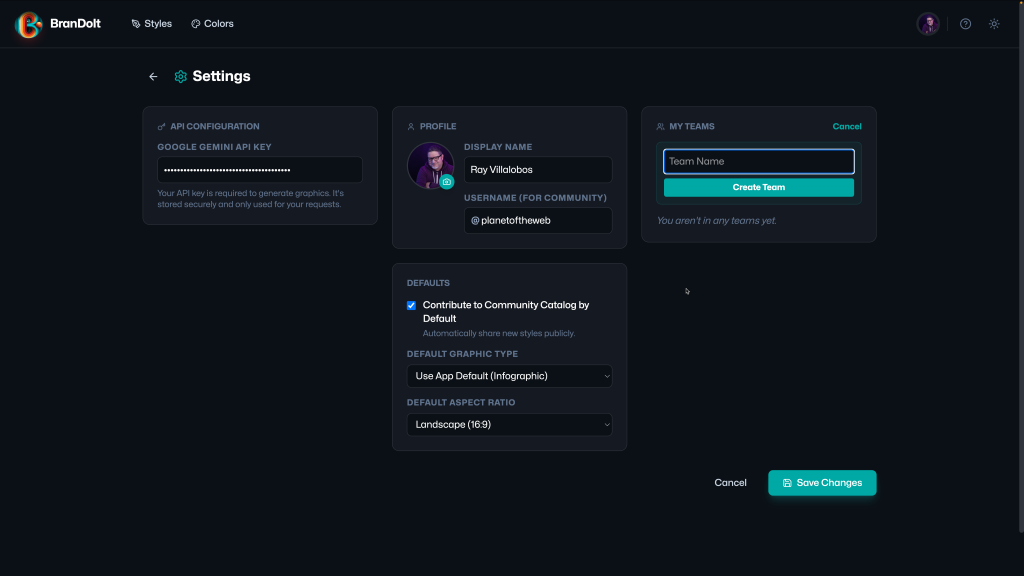

Identity shows up earlier than you expect

A prototype can treat people like a single user. A product cannot. The moment you want other people sign in, a whole category of problems appears that never show up in a chatbot.

Usernames need to be unique. Sessions need to persist. Login needs to be flexible enough to feel normal, like using an email or a username interchangeably. Each of those details touches state, permissions, and error handling.

A lot of companies don’t build most of their own systems for dealing with things like authentication, they rely on third party tools and platforms.

I leaned on Firebase Authentication and you’ll see other things, so I could focus on product behavior rather than password storage, session handling, and account recovery. It also forced me to think clearly about user state early, which paid off later.

Persistence becomes real

Early versions of the app relied on browser state and a feature called localstorage. That works when you are the only user and nothing needs to last very long. It breaks down the moment people expect their work to still be there tomorrow, on another device, or shared with someone else. That means implementing a database.

Moving to a real database forced decisions the prototype never required. What belongs to a user versus the system? What should be private, public, or shared with a team? Those questions define how people can safely use the product.

Again I leaned on Firebase with their feature called FireStore because it provides persistence without managing servers, and because its security rules sit close to the data model. That made it easier to reason about ownership and access, but also means you’ll have to learn to deal with access rules to control who has access to what.

Making the switch to product management

This sounds a bit silly, but I like the ability to upload a profile picture. It sounds like a small thing, but I appreciate when an app is polished enough to have them.

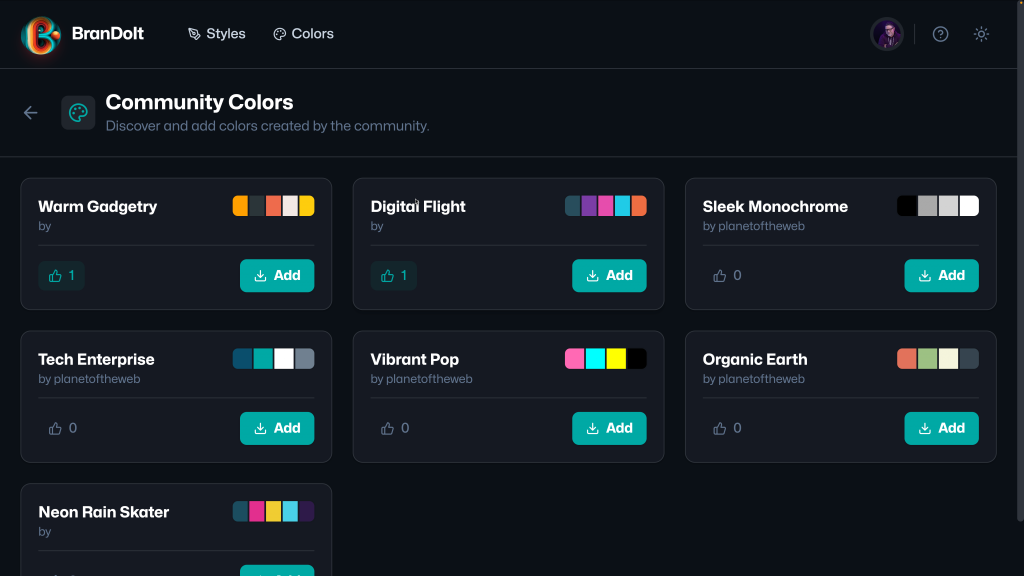

Vibe coding apps means that you start focusing less on the code and more on the product. You think of what features should this app has instead of how the heck am I going to build that. You constantly tweak functionality and add features like community colors and styles, the ability for people to customize all features and upvote styles they like.

I also added the ability to create teams so people could collaborate. I know the AI wrote a lot of the code, but features have consequeces.

As soon as I added file uploads, CORS entered the picture. CORS is a browser security mechanism that lets a server say which other origins are allowed to access its resources. CORS bugs are frustrating because they often look like random failures. Everything works locally. In production, the browser blocks the request and the UI just sits there unless you handle it explicitly.

Deployment is Critical

You need to decide where the app resides and how deployment happens, maybe consider the app’s URL, since most vibe coded apps will have horrible URLs. To do this, I decided on a platform called Render.

Render was a good fit because it handles builds and deploys with minimal setup, but it also made configuration mistakes very visible. I added configuration checks and clear messages for missing setup, because the alternative is an app that looks fine but does nothing.

However, Hosting the app on Render exposed the gap between code and configuration. Environment variables behave differently depending on whether they exist at build time or runtime, and assumptions that work locally can quietly fail in production.

This is probably an area I might reconsider. I started with having Google Cloud services host the app, but I found it too cumbersome to do things. I moved on to Render which was a dream for deployment, but it meant having the tool work with several different services.

I might consider doing things all in Firebase next time, however, Render does generate a simple URL appname.onrender.com, which although isn’t a custom domain, it’s close enough for this pseudo-product.

Cost turns ideas into decisions

In a prototype, it is tempting to use one API key and move on. In a public app, that quickly becomes a liability. If everyone uses my key, I pay for everyone’s usage, and abuse becomes easy.

For this reason, BranDoIt moved to a BYOK model, bring your own key. That single decision reshaped the UI and the experience. Settings needed to be explicit. Errors had to explain what was missing. Features had to respect whether a user was authenticated and configured correctly.

This is one of the clearest differences between prompting and product. A product needs a cost model, even if it is simple. When you use AIStudio to vibe code a prototype, you’re somewhat shielded from this. Gemini is also a great platform to work with since it’s extremely affordable.

What’s really different

The simplest way I can describe the transition is this. The prototype focused on output. The production app focuses on identity, persistence, ownership, security, reliability, cost, and deployment.

If you are coming from prompting or a vibe coding platform, that list can sound intimidating. It should not. It is not a wall. It is a map of what shows up when people start depending on what you built.

Advice for the transition

If you are thinking about turning a prototype into a product, these are the things I would put on your checklist early:

- Decide who pays for usage. Cost shows up faster than you expect.

- Add authentication before you feel ready. Identity shapes everything that follows.

- Move from local state to real persistence as soon as data needs to last.

- Explore different platforms that balance ease of use with trust to handle the difficult things.

- Expect deployment to challenge assumptions that felt solid locally.

None of this requires you to be an expert developer on day one. It does require shifting how you think about responsibility.

What turned BranDoIt into a usable app was not better prompts. It was learning the product layer: identity, persistence, security, cost, etc. The encouraging part is that once you learn that layer once, you can reuse it for every prototype that follows.

If you can prompt your way to a working idea, you are already most of the way there. The rest is learning how to make that idea dependable for other people.

If you want to play around with the code, fork or submit issues, you can check out the GitHub repo.